By Scott Naugle //

Tazewell is a messenger. Through his art, colorful and enlightening, he offers an alternative prism through which we may encounter our world.

The high wattage lights bleach the floors, walls, shelves and the people moving underneath searching for groceries and household items. The chain-store box is designed to speed along the transactions, pushing people in and out quickly, efficiently. Near the front of the store, an older man fumbles through the display of reading glasses, perplexed by the array of choices. A younger lady, 30 perhaps, notices and assists. She is drawn to his openness and patience in muddling through the situation. She eventually buys the glasses for him, a pure and simple act of kindness as a thank you to the gentleman brightening her early morning visit to Walmart.

Rows away, I watch Tazewell leave the store with new reading glasses in hand. I regret not walking over to say hello, but he is gone through the swishing automatic double doors.

Minutes later, Tazewell returns, his arms cradling several of his small creations. He finds the lady who assisted him with the glasses and places a ceramic figure in her hands. The response is a mixture of surprise and emotion. Her eyes fill with tears. “Hey, Mr. Tazewell,” shouts a man in the register line, “How are you?” Tazewell offers him gift as well.

For a moment, the white, impersonal light bouncing off the polished concrete floor transforms to a palate of warmer hues, momentarily refracting through the soul and kindness of an artist with nothing in his heart but the desire to spread a joyful vision through his work.

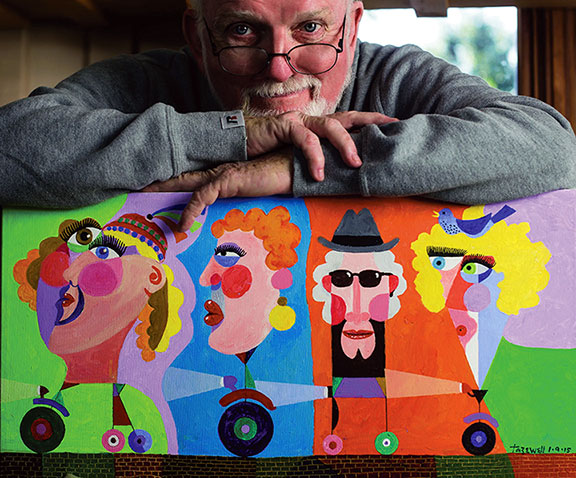

Tazewell Morton prefers to be known only by his first name. Born in Birmingham, Tazewell considers Pass Christian home. With his immediate family in Alabama, he spends solitary weeks working at his studio in Pass Christian. The small, octagonal cottage, dating from the early 20th century, boasts only a few creaky rooms, noisy plumbing, and marginal heating and cooling. Watercolors lean against the walls, small ceramic figures form rows on a folding table like soldiers lined for battle, and the dining table is covered in cut and painted wooden statues. There is a bed along a side wall. It too is littered with sketch paper and recently fired and glazed pieces. The indentation in the bed suggests where he sleeps alongside his work. Tazewell’s career as a big-city advertising executive and in academia are decades in the past.

Describing Tazewell as an odd man may allow the impression he is strange or dark-minded. He is neither, but odd in the sense I know of no one else like him who appears to live in a stream of consciousness. Tazewell follows the moment with an artistic muse as guide, eschewing convention or the constraints of expectations.

If there is a theme in the work of Tazewell, the watercolors and oil paintings, the ceramics, and the outdoor sculptures, it is one of bliss sourced in the freedom of spirit.

“All That Tazz” features four aquatic creatures, each playing an instrument, in a merry parade of music and gaiety. The alligator, as benign and as joyful an alligator that you’ll ever see, playing the saxophone. The lobster blows into a bugle. Between are two fish, alive in shades of greens, blues, and purples. Musical notes burst in gleeful passage from each instrument while all appear to be dancing in an aquatic ensemble of jazz. There is a sense of movement in the painting, the amphibians swinging and grooving to the riffs unleashed from their instruments in an improvisational melodious collage. The background is white, leaving the context to the imagination

Whether it is a Live oak with hundreds of Mardi Gras beads dangling from dozens of branches, a multi-colored hand kissed by a butterfly at the tip of a finger, or a line of smiling faces pedaling on bicycle wheels, there are commonalities within the prolific art of Tazewell, regardless of media. In many of his works, the main subjects are removed from any background. The central object, fish, elephant, person, or tree, lacks connection to a place or context. This frees the imagination to focus on the intricately detailed and colorful subjects, without any experiential or emotional baggage. Disengaged from the weight of the world, unmoored and lifted from expected or familiar circumstances, the effect is one of nudging the viewer into a world of cool breezes and rhythmic tunes, where no shadows darken the moment.

It would be inappropriately dismissive to view Tazewell’s work as nonsubstantive or regard it as superficial hang-above-the-breakfast table art. The skill in the fine lines and intimate details of his work reflect years of practice and thought. “I’m never satisfied,” he told me, “I’m challenged to do new things everyday.” As to what he hopes one will gain from his work, “I don’t know why people are not happier. I want them to be.” Tazewell does not mean this in a trivial and momentary way, but desires that we all see the beauty and joy possible in our relations with others and our natural surroundings. “I gave up stress years ago and choose a life in art as personal fulfillment and to show others it can be done.”

In the past few years, Tazewell’s work was exhibited in Atlanta, Mobile, Hartford and New York City. It is available locally in Long Beach at Blue Skies Gallery.

If it would be anyone other than Tazewell, there could be valid concern that advancing years will slow the flow of work. Other than a slight tremor in his hands, and the need for reading glasses to see closely as he works on canvas or ceramic, his energy and creativity are unchecked. He walks slower now than when I first met him 15 years ago, but then again, so do I.

Tazewell was challenged a few months ago to create a signature teacup and saucer for a local coffeehouse. Rather than offer a single design that could be mass-produced, he individually painted 24 cups and saucers. Each is wildly different. Multi-colored figures dance around the sides of the cup on one design. The saucer aligns with their feet. Hieroglyphic profiles surround another. A painted hand grasps the handle and inside the cup of a third. In all, days of work were poured into each cup and saucer. Through Tazewell’s intellect, the ordinary daily ritual of drinking a cup of tea becomes a commune with bliss through art, an extraordinary moment. The cups will be featured in an exhibition in Pass Christian later this spring.

“I knew who he was when he came in and sat down, but I did not want to disturb him,” explains Lam Hoang, a server at Hook Restaurant. “Eventually, he spoke to me, and for the next 20 minutes asked questions about me and it was clear his interest was genuine.” “Louie the Buoy,” a children’s book illustrated by Tazewell, came up. “He told me how he did it and explained the process of matching his art with the author’s story of a buoy near Henderson Point. He was the nicest man.” This is the artist-messenger for whom art is inseparable from existence. That’s Tazz.

4 Comments

Leave a Reply